After I got sick, I embarked on learning a skill I’ve wanted to learn since I was little: illustration. Art offered me a way to maintain my connection to nature after it became more difficult to physically be and move around outside. Not only did it maintain my connection with nature, it strengthened it exponentially, as I began paying more close attention to nature than I ever had before.

Observation

The first step in learning how to illustrate was simply learning how to notice subjects that might be interesting to draw. It was too easy to walk by a cluster of plants that might be actually fascinating to illustrate simply because, to my untrained eye, it looked only like a blur of green that all blended into each other. As a result, I first needed to learn a little bit about what made plants different from one another.

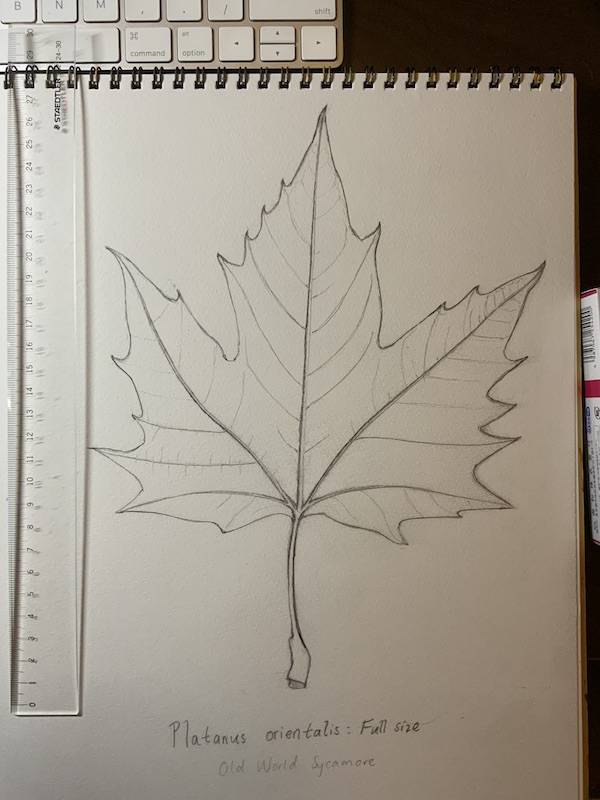

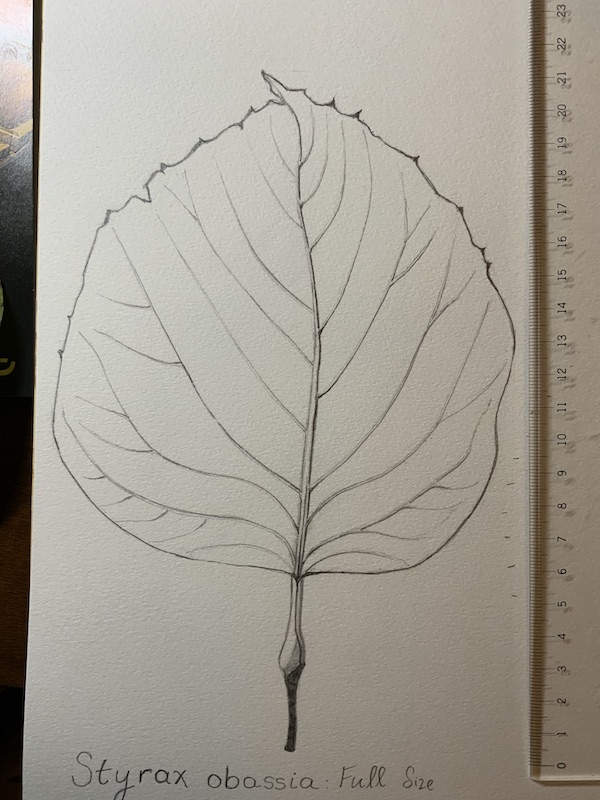

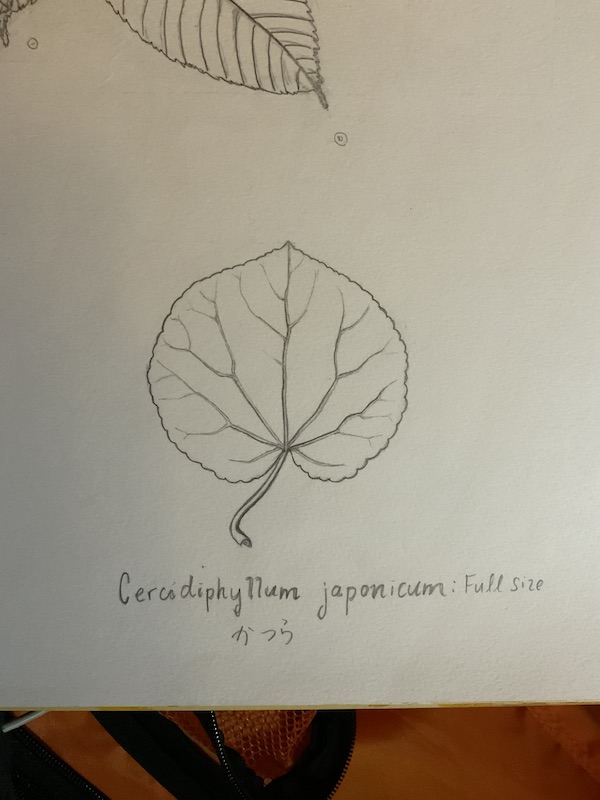

So I learned a little bit about botany and ecology – what structures make plants unique? Where might I expect to see some plants, and not others? I did this by getting a few good field guides and sitting myself down in various spots to see how many different plants I could identify. Though it took some time, it eventually helped me to train my eyes when I was outside, so that instead of seeing a blur of green plants, I could pick out Sawara from hinoki trees, mahonias from kerria. I made very simple sketches of the shapes of the leaves, made measurements of their lengths, and made notes about their textures, smells, and where they liked to live.

At times, this was a challenge because of the double vision I experienced. It meant I had to spend longer to get my identification right, and to know when to give my eyes a break or call it done for the day. This, of course, could be frustrating. But what good would it do if I strained my eyes so that my vision would be even more blurry for the next few days, meaning I couldn’t illustrate at all?

Ultimately, I later discovered that this kind of sensitivity to my body, patience, and knowing when to stop would help me as an illustrator. I had very little conception when I began of how time-consuming and challenging getting a drawing right could be – and that the difference between getting it right and ending up with a drawing I was unsatisfied with was often how willing I was to take the time I needed to get something right.

Light and Shadow

After learning how to notice what was around me and getting familiar with a few species, I could then start making more detailed observations of each species. Specifically, I became interested in how much information light could give me about a plant.

If the light hit the surface of a leaf and diffused evenly, the leaf was more likely to be smooth – particularly if the leaf was thick and leathery.

A leaf could be smooth, but if it was thin and more likely to wrinkle, the shine of the light wouldn’t be consistent, but interrupted by small patches of darkness where the leaf’s wrinkles bent away from the light.

Light and shadow could tell me a lot about the leaf’s veins from afar too. If I could see that the central vein of a leaf – called the midrib – cast a shadow, it meant I was probably looking at the back of the leaf. There, veins often stick up from the surface of the leaf rather than lying flat, like they usually do on the front.

Before long, my eyes slowly grew trained to how the light interacted with the surface of a leaf. On days where I was too tired to get outside, I’d look out the window and find myself making observations of how the light hit certain objects, doing my best to remember just in case I would want to illustrate them one day. The days I couldn’t go outside because of more limited mobility were often frustrating, but I was always thankful to have plants I could see from the window, and for the small herbs I had growing inside. It meant that even on those frustrating days, I could keep learning and practicing.

Color

Color took me the longest to understand, and is something that I am still learning something new about every time I illustrate. The leaves of one of my favorite trees, the camphor tree (also called kusunoki) undergo a beautiful change of color as they mature – from a pinkish-red when they emerge, to a lime green when young, and finally a deep green when mature.

Until that point, I had always associated red in a leaf with old leaves, ready to fall from a tree’s branches in autumn, rather than with new growth. But when I actually started looking, I noticed that several species in my neighborhood also had new growth that was red. I later learned this was because of the presence of high levels of anthocyanins (or pigments that can appear in plants as red, blue, and purple) in these leaves, which are thought to either help protect new growth from the sun and/or discourage insects and herbivores from consuming new growth.

I realized that, for me, illustration is an exercise in checking my own mental image of something – whether it be a plant, a landscape, a person, etc – against reality. This meant that in my head, I had always assumed new plant growth would be green – but when I actually looked at reality, I realized my mental image had been flawed/incomplete. Sometimes my mental image of something is correct – other times it is not. Discerning the difference is a skill that needs practice, a skill that helps me both in illustration and in other aspects of life. When I learn my mental image of something is wrong, it’s not necessarily a bad thing – more often, it’s exciting, as it reminds me that if I create something that I sense is not quite right, the primary problem is often just missing information.

Adaptation

I still learn something every time I illustrate – and each time I do, it brings me closer to nature and what I’m observing. It sometimes requires more patience than I have – it is always difficult when I use some of my limited energy to work on a piece that doesn’t turn out well. But other times, when what I’m working on seems to magically pull itself together, or I figure out a way to represent a tricky texture, I try to remind myself that it didn’t come out of nowhere – but rather out of all of the mistakes and “failed” pieces I did before and walked away frustrated from.

Navigating the world of illness and disability takes so much adaptation – adapting your own conceptions of yourself, your goals, your plans for next week that may have to change if you have a flare up, etc. And sometimes that process of adaptation never ends – sometimes you are continually adjusting your baseline, getting acquainted with a new set of symptoms or physical and mental reality, and reassessing what and how you can do things.

Illustration also involves a lot of shifting and adapting – like what happens when I’m 15 hours into a project and realize my proportions are actually completely off, or that the shade of green I’ve been using is actually way too bright? For me, it’s rarely ever a straightforward process. It moves on its own timeline too – sometimes I start off hot on a project, but then put it down for three months, only to pick it up again and have it turn out better than expected. To me, this mirrors my own experiences of disability and illness. Illustration doesn’t solve anything for me on those fronts – but it’s like a companion, one that understands how messiness, struggle, frustration and pain can go right alongside beauty and joy and connection. The way my mind and body works makes sense to it, because it also operates that way – and in that world, where we both start and stop and lay down and cry and laugh and look on in awe, I feel at home.

By Disabled in Nature