Disability is found wherever human beings are. Far from being an uncommon or extraneous occurrence, 1 in 6 people worldwide are disabled, totalling 1.3 billion disabled people. While disability is widespread and is found among all demographic groups, it is far from evenly distributed.

For example, 80% of the world’s disabled population live in the Global South. Worldwide, Indigenous disabled people are particularly impacted: in Nepal, over 50% of Indigenous people are disabled; in Australia, that rate is 47% among Aboriginal women. In the United States, Indigenous people are more than 50% more likely than the national average to have a disability. Even this number is likely an undercount, given the systemic discrimination and barriers to diagnosis and treatment that Native Americans face in healthcare. This is no coincidence: colonization and imperialism, in addition to feeding the engine of climate change through extractive and exploitative environmental practices, cause intergenerational trauma, poverty, and physical and psychological violence that often result in disability.

Poet, writer, and disability justice advocate Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha takes this even further, linking disability, climate change, mass incarceration, and colonization together in their book “The Future is Disabled.” “More and more people are locked in prisons, both the regular kind and immigration detention, especially as the climate crisis pushes masses of people to flee land they can’t live on anymore, because it’s too hot or too flooded or too politically unstable because of the famine and stress caused by these things. Prisons are spaces where people get disabled, or more disabled. Wars continue, as does settler colonial displacement in Palestine and global Indigenous communities, the wages of which are disabled conditions from amputation to PTSD,” they write.

The Outsized Toll of Climate Change on Disabled People

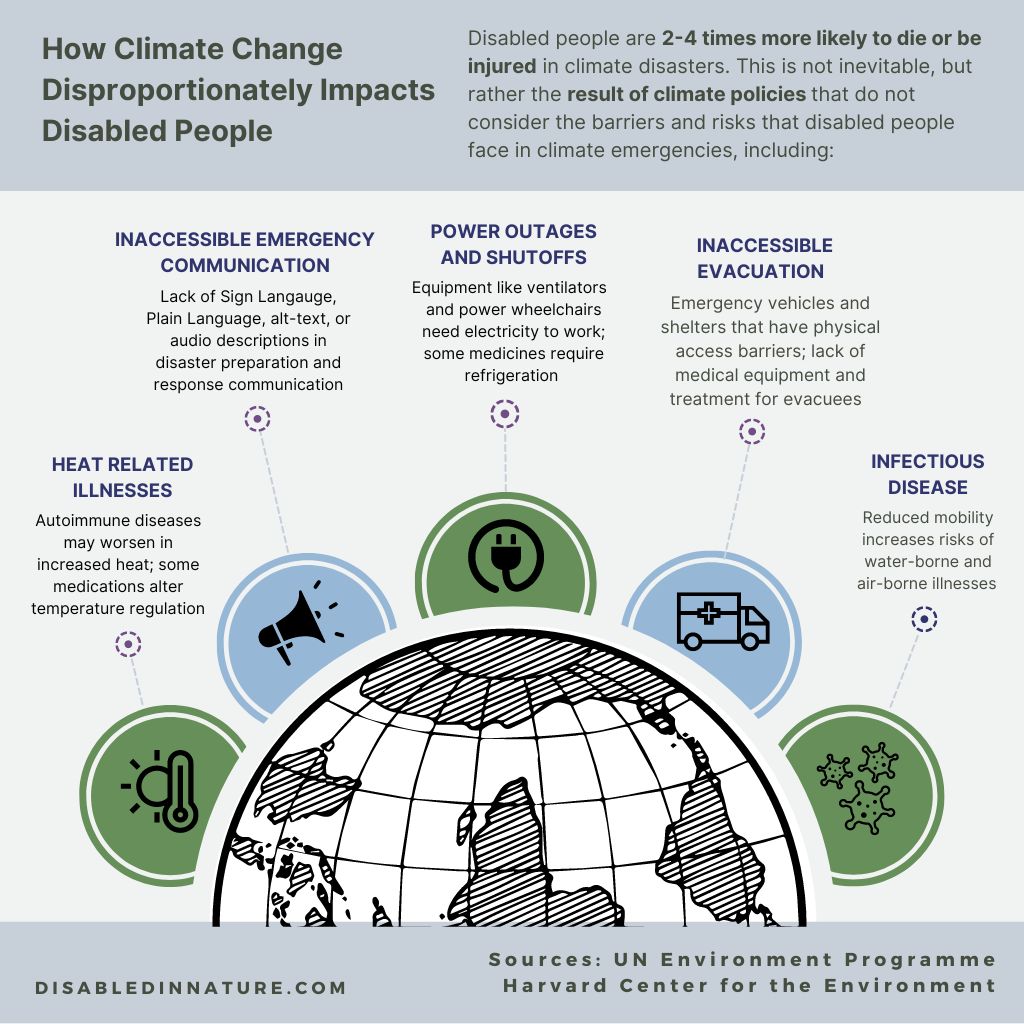

Just as important as understanding how climate change causes disability is recognizing how disabled people themselves are impacted by climate change. People with disabilities are 2-4 times more likely to die or become injured in a climate disaster than their nondisabled counterparts. Disabled people face unique barriers in emergency situations caused by a lack of inclusive climate preparedness policies, including:

- Emergency and evacuation transportation like busses and ambulances that are not accessible to wheelchairs, other assistive devices, and do not allow service animals

- A lack of backup power sources during shut-offs and outages during winter storms and heat waves for disabled people to access in order to charge power wheelchairs, ventilators, and to keep medications like insulin cool

- A lack of cooling and heating stations during extreme weather events for people who do not have access to climate controlled spaces

- Emergency communications and notices that are not accessible to Deaf, Hard of Hearing, and blind people, as well as those who are intellectually disabled and need Plain Language resources

The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs reports that worldwide, people with disabilities are left behind in emergency response efforts, and that 75% of disabled people “do not have adequate access to basic assistance in a crisis situation.”

Disability Exclusion in Environmental Advocacy and Education

Although disability is fundamental to understanding the multitude of injustices and impacts of the climate crisis, very few environmental and climate organizing and education efforts incorporate (or center) disability or disabled people in their goals and practices. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that of 1682 articles published on climate change response, only 1% incorporated considerations for disabled people. Despite the clear evidence that disabled people, particularly those who are also Indigenous and live in the Global South, are bearing the worst impacts of climate change, disabled people continue to be left out of climate change talks, including those held by United Nations Convention on Climate Change.

This pattern of exclusion is found not only on the global level, but also on the local and regional level. The exclusion of disabled people from climate and environmental related advocacy and education efforts is multifaceted and has many causes, including:

A lack of understanding and education about disability as a political, social, and cultural identity.

Contrary to dominant models of disability that position it as an individual problem to be solved, understanding disability as a political identity helps us to see how policies, practices, and institutions construct barriers to social, cultural, and political participation and thriving among people whose bodies and minds fall outside a constructed “norm.” Education about disability as an identity can help us see how climate-related deaths and injury among disabled people is not a fact of nature, but the result of choices, policies, and systems that are built around some kinds of bodies and minds but not others. An understanding of this can help environmental and climate movements engage disabled people as members of a community central to understanding and combating climate change.

Eco-ableism, or “a form of discrimination toward individuals with disabilities through an ecological and environmental lens.”

Eco-ableism frames disabled people as poor environmentalists if they:

- Need to drive vehicles because no other form of transportation is accessible, available, or affordable to them

- Cannot partake in some outdoor activities and hobbies popular among people in the field, or do them in ways that require mobility equipment.

- Advocate for accommodations and structural changes within environmental institutions to increase accessibility that may mean making structural changes to parks, trails, visitor centers, etc.

- Require single-use plastics in their medical care or in their everyday living

Exclusion in environmental education, research, and training.

A literature review published by Salvatore and Wolbring in 2022 found only 27 academic sources that described disabled people as being engaged in environmental education. Of those 27 sources, the vast majority referred to disabled people as only learners of environmental education, and not teachers, curriculum designers, knowledge producers, or advocates. What does it mean that disabled people are positioned only as students, and not experts or producers of knowledge? Environmental education is fundamental in shaping the next generation of environmental advocates, researchers, and policymakers that will affect climate policy. In order to address the vast societally-caused inequities and harm disabled people are facing as a result of climate change, it is crucial that more disabled people are in the room when climate policies, research, and preparedness plans are being crafted. The norms and practices of environmental education must reflect this reality.

Disabled People Play a Critical Role in Our Climate Future

Aside from the implications for equity, environmental and climate movements ignore the disability community at their own peril. Disabled people, particularly BIPOC, queer, and trans disabled people, can bring crucial insight about flaws and potential solutions to the systems that are perpetuating the climate crisis as people who are most affected by those systems. As Patty Berne and Vanessa Raditz write, “The history of disabled queer and trans people has continually been one of creative problem-solving within a society that refuses to center our needs. If we can build an intersectional climate justice movement—one that incorporates disability justice, that centers disabled people of color and queer and gender nonconforming folks with disabilities—our species might have a chance to survive.” Ignoring the disability community, then, means climate movements depriving themselves of the ingenuity, creativity, and insight needed to understand, combat, and adapt to the realities of climate change.